|

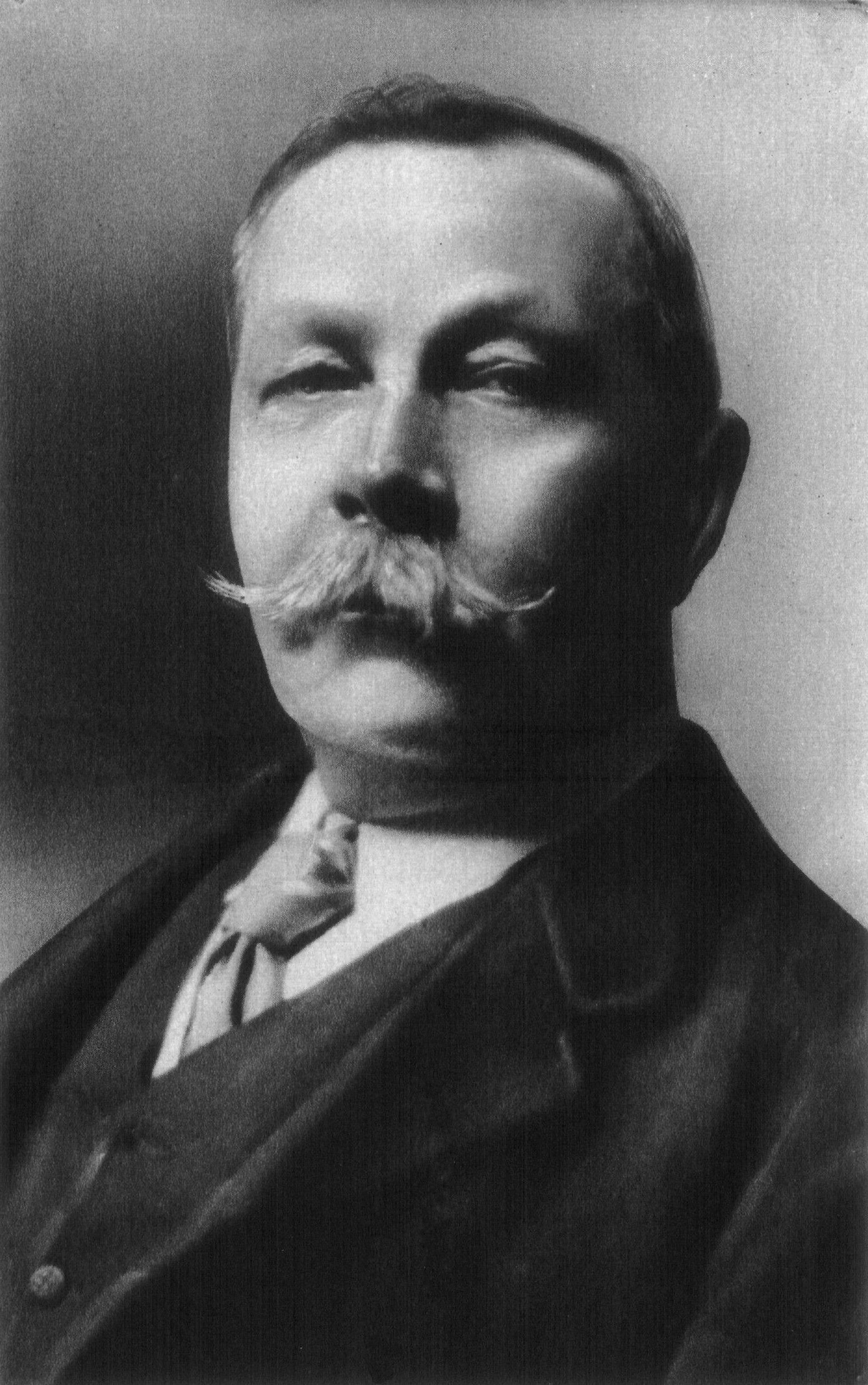

| Sir Arthur Conan Doyle |

The estate of Scottish author Sir Arthur Conan

Doyle has advanced a

creative -- and controversial -- legal argument, in a gambit to

protect its rights to continue to control licensing the fictional personae of Sherlock Holmes and his

sidekick Dr. Watson,

for at least several more years.

Conan Doyle authored four novels and 56 short stories featuring the now

iconic literary characters of Sherlock Holmes and Dr. Watson between 1887 and

1926.

Under UK copyright law, Conan Doyle's entire corpus of work is now

freely in the public domain.

However,

under more restrictive US copyright law, only Conan Doyle's works published

before 1923 are now in the public domain, whereas 10 of his works published

after 1923, such as the "Case-Book

of Sherlock Holmes", remain squarely under US copyright

protection until as late as 2022.

Many critics

vehemently argue that the US copyright system, which currently grants authors' heirs a monopoly on their ancestors' written works for as long as 70 years

after the author's death, is too restrictive. In any

event, the American public is now confronted with can be legally done with a partial catalog of freely

available Holmes-related texts.

|

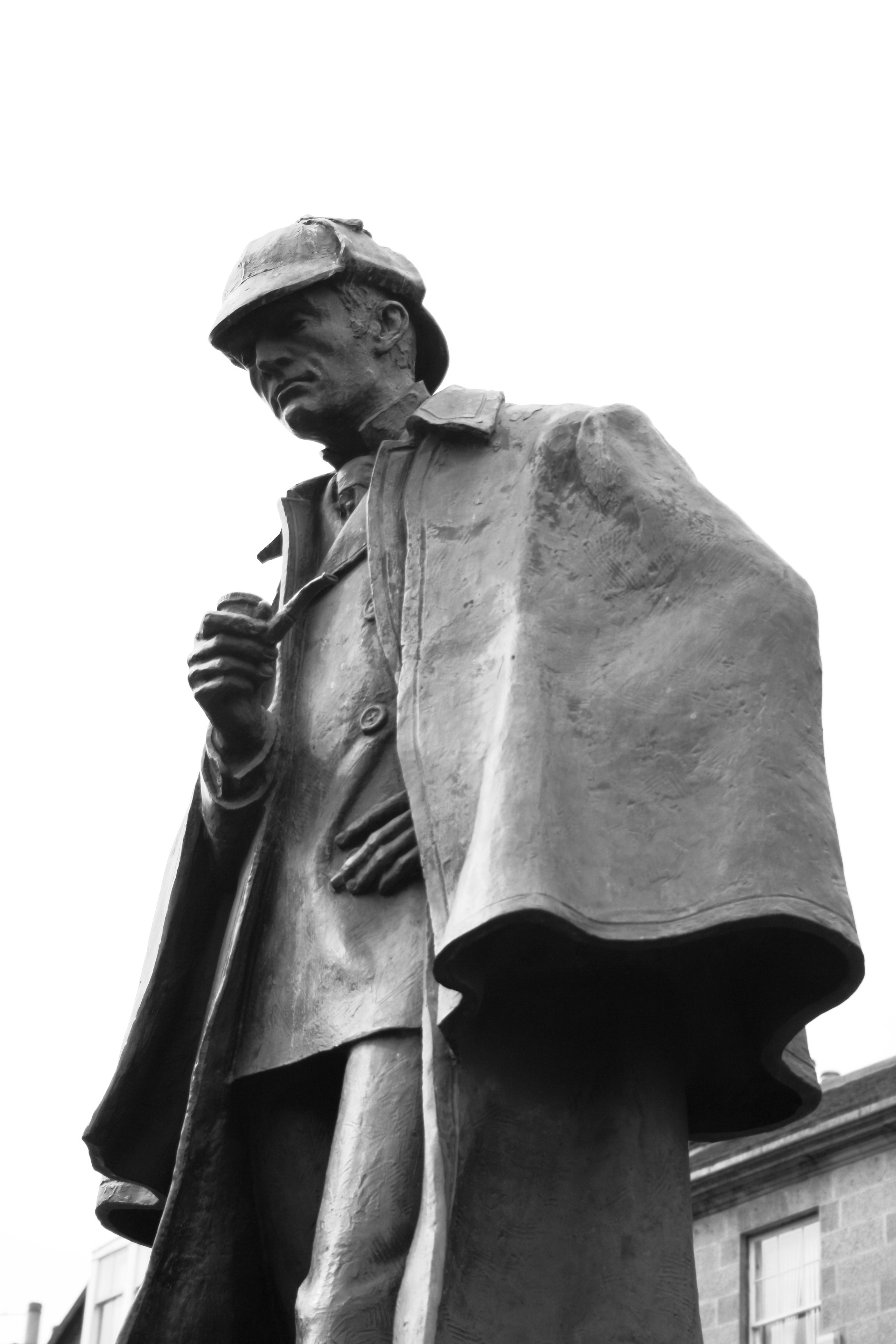

| Statue of Sherlock Holmes in Edinburgh, Scotland |

A Los

Angeles-based Sherlock Holmes expert and entertainment lawyer, Leslie Klinger, recently filed a

declaratory judgment suit in Chicago federal district court,

seeking a ruling that the characters of Holmes and Watson are now effectively freely in the public domain for anyone to use, regardless of whether a few of Conan Doyle's final works still

remain under US copyright protection.

The Conan

Doyle estate argues that the entirety of these literary characters should remain under

lock and key, until the final of the books' copyrights expire. The estate bases

its argument on the logic that the characters' entire personalities, including

subtle quirks and flaws, were developed in later works and are therefore

embedded throughout the entire corpus of Doyle's literary contributions. To separate characters into "earlier" and "later" would be to artificially dissect them.

This interesting case raises complex issues of unsettled copyright law.

For example, if a complex literary character "evolves"

throughout many different copyrighted texts written during an author's long lifetime, as each text passes into the public domain many years after her

death, does only the "immature" character become free to copy, until

the entire corpus has lapsed?

Alternatively,

once the first of many book's copyright expires, is the entirety of the

later-developed character fair game for the public to take?

The

question is not entirely academic, as Conan Doyle's estate could theoretically

block the making of a television show such as "Elementary," which

sets the detectives in modern-day New York, unless the estate is paid a hefty

royalty. The estate could also have blocked a new movie similar to the 2009 film starring Robert Downey, Jr. and Jude Law.

On this issue, the Conan Doyle estate faces a challenging legal landscape. In 1999, the Second Circuit Court

of Appeals confronted a virtually identical issue, and refused to rule that entire characters remained under copyright monopoly when significant previous works had lapsed into the public domain.

In that

case, the appellant had wanted to create an unlicensed Broadway musical using the

characters of "Amos 'n' Andy." Radio programs featuring the

characters from 1928 to 1948 had lapsed into the public domain. However,

several later-created television shows remained under copyright

protection.

The New York-based Appeals Court found that this latter fact was not dispositive. In that case, the Appeals Court held that Silverman, who had wanted to

utilize the characters freely, "should now receive a declaration that he

is entitled to use all aspects of the "Amos 'n' Andy" materials,

including names, stories, and characters, to the extent that such elements of

expression are contained (or, in the case of characters, to the extent

delineated) in the pre-1948 radio scripts, which are in the public

domain."

In other words, the fact that some later materials remained

copyrighted did not entitle the copyright owners to continue to monopolize the characters, as

large aspects of their personae had been developed and become public domain years

earlier.

The New York-based Appeals Court also found that no valid trademark rights in the characters

remained, as they were abandoned upon the radio shows passing into the public

domain. It is yet to be seen how the District Court and the Seventh Circuit Court of Appeals, based in Chicago, will rule on this topic in the pending Conan Doyle case.